Working furiously behind the scenes at MOTAT is the Registry Team. Based at our offsite storage facility, Registry is responsible for many things including maintaining the database system, object storage and location management. We often have many projects running at a time, including inventory.

But what is an inventory exactly? A museum inventory is defined by Mark Tabberas as “the process of systematically assigning a unique number to every object, locating the object within the building and matching the object with its historical or legal documentation. Inventorying organises and establishes what the collection is”.

In 2013, MOTAT received a series of Lottery Environment and Heritage grants from the New Zealand Lottery Grants Board which allowed the formation of the Collection Inventory and Digitisation Project 2013-18. The purpose of the project was to provide a comprehensive inventory, accessioning and digitisation program of the MOTAT Collection and associated documentation.

Over the course of the project, 12,353 temporary records were created in Vernon (our collection database) 11,862 objects were inventoried, and 12,020 images were linked to temporary records. It essentially created better tracking of objects, the matching of parts to objects, better collection care, and better access for curators to research and resolve object statuses.

A temporary record is an object that cannot yet be matched to an accessioned object in the database. This is because it was not labelled or recorded accurately. Instead of giving the object an accession number, it is assigned a temporary number (or T number), until further research can be undertaken into the object.

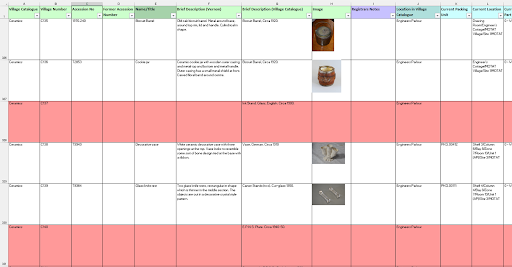

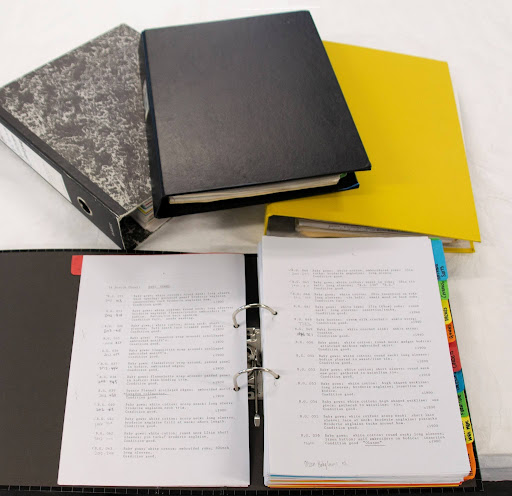

The Inventory process is still ongoing. In 2023 we started to tackle some of the spaces where objects have been stored in the Victorian Village. In early MOTAT days, the Village Volunteers recorded objects in the Victorian Village Catalogue. The catalogue consisted of both typed and hand-written records and multiple copies existed. In 2023 a master copy of the catalogue was created and digitised, allowing the entire catalogue to be found in one place, and it is now searchable. This means the whole team can use this new document to identify, match and resolve inventoried objects.

The Inventory Process:

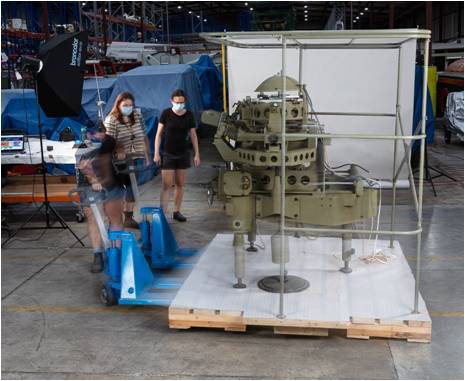

Recently the Registry Team has been working on objects that were found in the attic of Quinlan Cottage. These objects were stored poorly, with no accession numbers in sight. The team carefully packed and transported the objects to offsite storage so they could be processed.

Once they arrived at offsite storage, they were placed in a quarantine space, removed from the larger collection to help contain any pests (borer and silverfish for example) until we could process and treat these issues.

We then started to work through the boxes and pallets of objects, trying to sort through them based on where they came from. Many of the objects we inventory do not have any form of identification, and as they are often quite old objects, it can be difficult to determine what the object actually is. Each object has its own history, and therefore its own set of challenges. Let’s look at a few case-by-case examples to highlight the different things we have to consider.

CASE STUDY 1

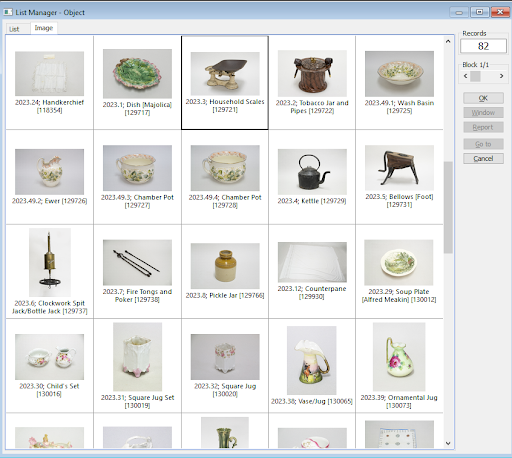

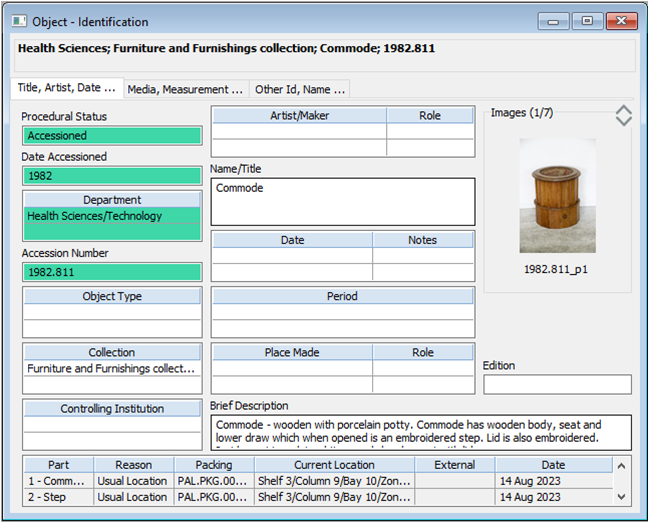

When the team sat down to inventory objects pulled out of Willow Cottage, we came across a commode. The first step during the inventory process is to search Vernon to see if we can find a match to an existing record.

Using an advanced search tool, we searched for key words such as “toilet”, “commode” and chamber pot”. You must think about what these objects may have been called fifty years ago, rather than what it might be called by today. So, using a broad range of keywords we enter that search, and exclude Library material, so we are only looking for objects.

Our search brought us to a small selection of objects. We can look at the image search to immediately disqualify objects. Selecting the ones that are of interest, we can look at these records closer to see if any of the descriptions match that of the commode we are looking at.

We found a record that appeared to match an existing record in our database. The unique embroidered details and the footstool feature make this object quite distinct and based on the details everything fell into place. We had a match! And so, an object that could have been given a T number was reunited with its accession number.

CASE STUDY 2

Whilst working on inventory of the Victorian Village we have come across a large number of objects with C numbers. These are numbers given to objects from the Victorian Village Catalogue. As an example we found a Majolica dish. A member of our team came across this plate, which had “C246” written on the base. This immediately indicated to us that this object was in the Village Catalogue. Using the digitised catalogue we can search this number, which brings us to the object. The description in the catalogue matched the dish we were physically examining and we could confidently call this a match.

Because the Village Catalogue objects are considered part of the collection, we immediately give found C numbered objects accession numbers. This means that instead of giving the object a T number record we create an accession record. This requires slightly more detail than a T numbered record, as this will be published on Collections Online and made available to the public. So, success! We have now created a beautiful new accession record to showcase this object.

CASE STUDY 3

This next case study is a recent example where we really had to dig deep and trust the process to figure out the context of this object. We first came across part of an object, which we couldn’t quite work out what it was.

The object was first found during photography, where a box was emptied, everything photographed and then laid out for inventory. It had a tag which implied that it was a “Spit” and found in the Household Accessories section of the Village catalogue. However, it wasn’t until a week later that this object was researched. Our team didn’t know much about spits, but we soon realised that we were missing parts.

We then came across another unidentified object in a different box, that also came from Willow Cottage. Upon further research we established that the two parts were a match, and that this object was a “bottlejack”. We were very happy to reunite the two parts, especially when we then found the key in yet another box.

A bottlejack, for those who don’t know, is a machine with a clockwork motor which rotates meat roasting on a spit. Success!

CASE STUDY 4

One of the great things about the inventory process, is that by creating a T-numbered record we have now created a digital record for the object, which means it is now searchable by our Curatorial Team. This allows for the objects to have further research undertaken, as well as be considered for potential display. This is happening more and more frequently, as we inventory more of the Collection.

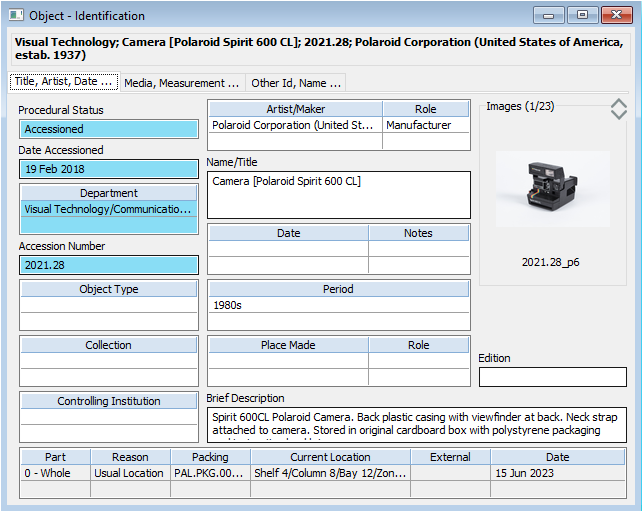

Let’s look at an example. This Polaroid camera was found during the inventory project and added to the Collection with a T-number in 2018. During the exhibition design stages of MOTAT’s previous exhibition, Love/Science, the curators came across this object in the database, and decided it would be a great fit for display. Since it was being displayed this indicates that it fits MOTAT’s Collection Policy, and so we converted it into an accessioned object.

The number was therefore changed from T11142 to 2021.28. This highlights how by inventorying the Collection, we can more easily see what the MOTAT Collection holds. It is also accessible to our teams to research objects further. In this case we had a great result, where upon further research, an object was deemed significant to the collection and therefore given the love and attention it deserves.

So, we have these happy endings. You’ve given an object a T number, you have matched an object to an existing record, or you’ve converted it to an accession number.

Then what? Why do we do this, what’s the point?

The point is – we are improving the database for future MOTAT. Once we have created or found the correct records, we need to improve them. Our motto in Registry is leave everything better than how you found it. We need to be leaving records in a state that means you could look up an object and find it in the system without needing an image. We want to give future MOTAT the best chance possible by having all the information handy. Whilst we still write a physical Accession Register the world has moved online, and we can capture so much more information than was possible 60 years ago when MOTAT started out.

So how do we do this?

1) We start by updating the Vernon Record for the object. In the past records did not contain a lot of information as they were created from the original catalogue cards which were previously used. Our job is to add as much information as possible. We update the description of the object, including manufacturer details, and where and when the object was made. We update measurements, part numbers, the medium of the object, as well as the classifications this object would fall under. We also add any text that is present on the object which gives key clues into the object’s history.

2) We ensure we flag that this object was inventoried, who inventoried it, and when. We add where this object has been inventoried from and we then give it a current location, for example the new box is it going to be stored in or a location such as the Quarantine Room.

3) We update the condition notes to give a clear indication of what state the object is in at time of inventory. Importantly, we flag any HAZMAT issues, the object might have, which is information that was not previously recorded before in the Vernon database.

4) We capture updated and good quality images of the object, including all its parts such as the box it came in, the text on the side, and close ups.

5) We label the object with a swing tag. If the object is accessioned, we use paraloid or pencil to place a label directly onto the object, following Conservation practices.

One of the more significant updates is the change in storage quality. For example, we have recently been working on objects that were stored in Quinlan Cottage’s attic. These were dumped in piles in disintegrating cardboard boxes with no labels, covered in dirt, dust, accretion, rat faeces and goodness knows what else. Once an object has been inventoried, we wrap the object in tissue or foam, and it is either strapped to a pallet or stored in approved tubs, which are packed out to avoid any jostling during transport. These are then stored at M3 where the Conservation Team can monitor the environmental conditions, and the Registry Team locates each item to a specific shelf. This way the object is far more likely to survive for our future visitors.

So, in conclusion, the inventory project will continue over the next few years, as we focus on the MOTAT Great North Road Site. You may see us moving around, hiding in dark corners and carrying strange objects. We are simply continuing our inventory project, moving things to M3 so we can work to the best of our abilities and get these objects into the database. Our long-term goals are to complete the Victorian Village Catalogue and finish the inventory of MOTAT Great North Road.

Whilst this work is progressing, T numbered objects will continue to be researched by the Collections Team, and as these case studies show us, this allows for more objects to be available digitally and physically for our internal teams as we continue to tidy up the cataloguing of the Collection.

By Emily Hames and Christen McAlpine

Comments